- Home

- Justin Deabler

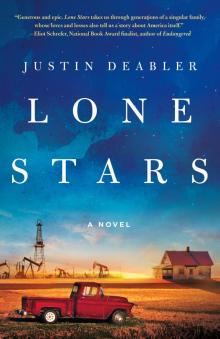

Lone Stars

Lone Stars Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my parents, and Mark, and our son

Prologue

The cry rang out through time and space. It shot down the hallway and into the bedroom, past the cats wheezing on the bed, over Philip snoring through his mouth guard, and pierced the hazy bubble of Julian’s melatonin tablet. He rocketed up to a sitting position, out of habit, and waited to see if it was a passing thing. Their son howled again.

“Your turn,” Philip mumbled and pulled a pillow over his head.

Julian squinted at the blue spectral glow of the baby monitor, lowered to mute because Pablo had a real set of lungs on him. He stood at the edge of his crib, facing the camera with an omniscient stare, and shrieked. “Hang on,” Julian sighed. He stuffed his feet in his slippers and hurried to the nursery.

The baby had worked himself into sorrowful hiccups. Julian picked him up, careful to bend at the knees and save his back, which could go out at any moment. He paced in a circle on the rug while Pablo fussed, and sang the usual songs. He couldn’t help falling in love, he began, singing like Elvis, like they heard in the hospital cafeteria the day their son was born. They walked some more. The rainbow night-light cast shadows around the room—the stuffed bear looming on the wall and the origami birds hanging from the ceiling, undulating to the current of the humidifier. The nightmares were a new thing, over the last few weeks. They sent Julian scrambling to Google in his own daddy terror, like the colic and stranger danger had sent him before, back when they rode into town—and then eventually moved on, like everyone said they would. But Pablo wasn’t everyone’s baby. He was theirs.

His hiccups softened to the occasional whimper, felt as a tiny hot breath on Julian’s collarbone. He went to the window and nudged the curtain open. The treetops in Prospect Park stood black against the cobalt sky, lit by a lonely moon. Julian’s throat tightened. He had to pull back at times like these and not think too big, about climate change and the world Pablo would inherit, or raising a kid to be good today amid all the noise. Pull back, he told himself, because now, tonight, life was so great it defied logic. How was it possible—after all the struggles of growing up, and so much loss—that Julian could enter the nursery, and Pablo could gaze up under a halo of black curls, and suddenly everything that came before made sense?

Julian looked down at a book on the windowsill. The Story of Pablo, it said in round letters on the cover, with a smiling dark-skinned cartoon boy and two white cartoon dads. It had come in the mail the day before. He would soon be old enough to understand when they read it to him, about the mom who loved him so much when he was in her tummy that she gave him to her older friends Julian and Philip to raise.

“What will you tell him?” Philip had asked when they leafed through the book that afternoon, during the baby’s nap. “About your family?”

“What do you mean?” Julian replied.

“Well. He sees mine all the time. He’s met his birth mom. But your mom and dad. What will you tell him?”

“I don’t know. Stories.”

“But which ones?” Philip persisted. “History is about the future. What will you tell him about where you came from?”

A streetlamp flickered outside, on the park. Pablo shifted on Julian’s chest, maneuvering his thumb into his mouth, and sighed peacefully. The world was silent again. Out of nowhere Julian remembered a painting he saw many times as a kid. It was one of his mom’s favorites, a Magritte at the Menil Collection in Houston. He and his mom used to stare at it for what seemed like hours: a painting of a house in both day and night, a blue sunlit sky at the top, until the eye traveled down to the dark roof of a house, and shadowy trees, and a streetlamp in the nighttime.

Gently Julian kissed Pablo’s head and looked out at the park. He thought about the night, and dawn, and his mom and dad and other people who were gone. And he wondered—which stories to tell?

I.

Love

1

The Man with the Muddy Boots

For the first time in her life, Lacy Adams paid attention in church. There was nothing special about the service that Sunday. Her dad sat beside her, blank-faced as usual. Junior doodled in the hymnal. Her mom fanned the wet Gulf air blowing in from Harlingen, while the familiar calls of green jays floated through the open windows. But that morning Lacy felt different. She had just learned the scientific method at the end of the school year, and her teacher said it applied to everything but the Bible. And ever since then Lacy had looked at the world with narrower eyes, tingling with a sense that asking questions, using her mind, could unlock mysteries around her. She sat forward in the pew and listened. The pastor told the story of beautiful Queen Esther, a Jew in a hostile land who loved her people and saved them from slaughter when she revealed herself as one of them. And now, today, the pastor preached, let us pray for the freedom-seeking people behind the Iron Curtain, under the soulless Soviet grip, who have to hide themselves like Esther to survive.

After the sermon, the congregation rose to pass the peace. Lacy and Junior hopped to their feet, but they could never reach any hands to shake. The Adams family had a pew reserved for them, front and center, and no one sat in the pew behind them—a distance the farmers kept out of respect, Lacy knew, to give her family more of God’s light. She watched her parents lean over the empty pew, but when her dad stuck out his hand and said, “Peace be with you,” a farmer with a thick beard just stared at it, keeping his own calloused hands on his belt buckle. “Not while you’re still around,” the man growled, loud enough to hear, and turned his back to them.

Her dad didn’t blink. He turned to his wife and shook her hand, and then Lacy’s and Junior’s for good measure. The service resumed. Lacy could tell that her mom was seething, but she didn’t speak as they filed outside and piled in the red Buick and drove home. She held her tongue while she warmed the pot roast and set the table. She led them sharply through grace. “The nerve,” she huffed when they started eating. “The disrespect, inside First Baptist? After all we’ve done for them, to refuse to shake your—”

Lacy’s dad lifted his hand for silence. The family watched him sweep the last bites off his plate and run the good linen napkin over his mouth. “They’re blowing off steam, Mary,” he said, standing up. “Two days and it’ll be over.” He had changed before the meal, out of the Sunday suit and snakeskins he got in Houston, into dungarees and work boots. He settled his Stetson on his massive gray head and went out the door without a look or goodbye.

“Pure white trash,” she resumed, talking to no one in particular like she did at the table and in the car and whenever Lacy’s dad wasn’t around. She smoothed the blond hair she wore in a fluffed-up Grace Kelly style. “None of those fools had to sell to your father. Drowning in debt, and he bailed them out and gave them jobs. Couldn’t grow corn in Eden. Do you see your daddy taking a day of rest? Ten years he’s worked on the Plan—the feedlots, cattle, sticking his neck out—to change how America eats. Pure disresp

ect.”

“Can I have some more—” Lacy began.

“No, ma’am.” Her mom slid the bowl of potatoes out of reach. “You’ve got to reduce to look good for your Girl Scouts pageant. Junior, you want seconds?”

“Yes, please,” he said, and shot a wary look at Lacy.

“Is your troop ready?” her mom asked, serving Junior a heap of mashed potatoes. “Y’all just got the one more singing practice, right?”

“I guess,” Lacy said impatiently. “But first I have to turn in my family tree to get my Family History Badge. It’s due tomorrow.” She hated Girl Scouts. It wasn’t her choice to go, and she never wanted to mix with the uppity town girls. But anything Lacy did she did full steam, and for two weeks her mom had put her off, saying some other day they’d do her tree. “I can go get it,” she said.

“Manners, Lacy, not at the table.” Her mom sighed irritably and stabbed her pot roast. “I already told you about my family. I was orphaned, working in a washateria in Laredo when your daddy came in on a business trip with a tear in his shirt, and I had a needle and thread. Then we got married and had y’all two blessings. The end.”

“You were born in Laredo?” Lacy persisted. “I need your birth date, and your mom and dad’s names, birthplaces, and birth dates, to finish—”

“Write ‘deceased,’” her mom snapped. “Junior, how was Boy Scouts this week?”

“OK,” he chirped. “Wanna see what we did?” He wiped his face on his sleeve and jogged to the foyer. Junior was as cute as a puppy, with blond hair as light as their mom’s, not like the black mop on Lacy’s head. He charged into the room, doing an elaborate fall-roll-and-point maneuver, and aimed a pretend gun at their mom. “Kill the wetbacks!” he shrieked, spraying the table with rounds of fire.

“Junior!” their mom scolded. “Get up. Don’t say that word again.”

“What word?” he asked, rising in confusion.

“Wetback. It’s ugly. And no running in the house.”

“But that’s the name of the operation,” he objected. “Operation Wetback. We met the Border Patrol in Boy Scouts. They’re doing sweeps now. They started in Brownsville. Now McAllen, up the river to Laredo, all the way to El Paso.”

“And we like Ike,” their mom pronounced. “We always support our president. But.” She straightened her place mat. “Not all Mexicans are bad people, Junior. Some of them don’t want to blend in and be American, speak English or eat our foods—”

“Animals,” he barked. “That’s what the patrol man said. Live like pigs and send our money to Mexico, and we gotta get rid of them. He asked the Scouts what we think. I said build a big wall. With swords on top to stick them if they get all the way up.”

“Get rid of them?” Lacy said, slightly disturbed but masking it in the superior tone she had to take with her brother sometimes. “Listen, nosebleed, your patrol guy is talking about us.”

“Excuse me?” her mom blurted. “What on earth are you talking about, Lacy?”

“Our farm?” she said, suddenly filled with doubt at her mom’s tone. “Daddy’s business. His workers are Mexican, aren’t they? Like Xavier, he’s from—”

“Oh,” she sighed. “Yes, a good number of them.”

“Because one of the town girls,” Lacy muttered. “In Girl Scouts.” She bit her lip, unsure if she should continue but needing to test hypotheses. “She said Dad’s filling up the county with cow shit and Mexicans. And ruining everything.”

Her mom watched her and then leaned forward and asked, in a not-friendly voice, “Do you know what a pioneer is, Lacy? The man with the polio vaccine? Henry Ford? Thanks to your dad we’re going to be rich. We are rich.” She put a finger to her lips like they had a secret. Her eyes blazed. “But this week we’ll be really rich. Junior, you, me—the three of us. And we’ll move into town where we belong.”

“Mommy?” Junior asked softly. “Is the Border Patrol coming here, for our men?”

Lacy watched her mom’s knuckles whiten as she squeezed the napkin in her fist. “Don’t worry about that,” she replied. “Your daddy’s got it all worked out.”

* * *

Lacy’s mom had been talking about the Plan for as long as she could remember. Her mom kept to herself and didn’t have friends, so when her dad was away, which was most of the time, Mary Adams talked to her kids in a low, steady stream, like a faucet left a little on. For years their dad had been buying up the farms near McAllen and clearing the crops and trees to build the feedlots. He shipped cattle in, fattened them, and sent them to slaughter, and after ten years he hit the impossible number: a hundred thousand heads, with the facilities and staff to sustain them. He met his target—her mom always talked targets during meals—and could sell to a company in Chicago, and they were finally leaving this stink patch for a big brick house her mom had picked out. Because that’s how America works, she would say as she cooked or folded laundry—you get rich and stay that way, and your kids stay that way, your grandkids, on down the line.

Lacy had nothing against McAllen, with its grand paved streets and palm trees reaching for the sky. But she and Junior didn’t share their mom’s excitement, or really believe they were moving, because the farm was what they knew and it was fun. As soon as Junior could walk, he and Lacy played together. After school and summers they spent side by side, climbing the fence posts to watch the cattle storm the troughs at feeding time. Or they’d play their favorite game, seeing who could get closer to the bank of the manure pond before one of them gagged and ran away, coughing and giggling in a sick ecstasy. On clear days they climbed the only tree for miles, a cottonwood beside their house, and surveyed the dirt squares stretching to the horizon, full of cattle barely moving as the sun beat down. Lacy told Junior what she learned at school as they perched on a branch, photosynthesis or the Boston Tea Party, so he’d be the first to know in his class. They were best friends.

But the last few months, something seemed to change between them. Lacy knew for sure on the day they saw a calf being born. One morning at the end of the school year, their dad woke them up and they ran to the barn to watch. For an hour its head peeked out of its mom’s rump, waiting as the sun rose, opening its mouth silently like it didn’t know the words yet. The cow lowed as her calf’s legs cleared and it fell into a bright new world. It staggered to its feet. Lacy held her breath, scared to interrupt the sacred scene. “How long till it’s fat enough to kill?” her brother asked.

“Junior!” she cried. Because it was the last prick of what had been building for a while. From the moment their mom signed them up for Scouts, her brother started acting like another person. He didn’t want to play with her much, and when they did, all he talked about were boys in his troop or killing things. Or he’d lecture Lacy, fresh out of first grade while she was through fourth, and when he got things wrong and she corrected him he’d cut her off with the same line—“You’re a girl”—and ride away on his bike or shut his bedroom door. And that was how things stood between them soon after, on the Sunday Junior fired at their mom in the dining room.

Lacy couldn’t put her finger on it, but something didn’t sit right when their mom said stuff got worked out with the Border Patrol. Lacy didn’t make a habit of questioning her parents. She loved them. Her mom was the prettiest lady she knew, with a big twang and bigger smile—a real Texan woman, a teacher told her once. And her dad had muscles, even though he was old, and a face as strong as Mount Rushmore in her history book. But there was a look in her mom’s eyes at lunch that Sunday, a sound in her voice, that made Lacy excuse herself from the table to go find Xavier.

Next to the barn she saw the truck he used to shuttle workers from Chilitown to the feedlots every morning and back again at night. Xavier came out of the barn carrying a couple of cattle prods. Lacy knew she’d find him. He was her dad’s right-hand man, and if one of them was working, so was the other. Xavier was a good guy, her dad said, and there was something Lacy trusted in his mellow voice and the pressed d

ungarees and clean white shirt he always wore. He smiled as she approached, his hair so black in the sun it shined a little blue.

“Muchacha.” He dropped the prods in the flatbed. “Want to drive the big truck?”

“Hi, muchacho,” Lacy replied. Junior’s recent indifference to Lacy had left her with more time on her hands, and lately she spent it tracking down Xavier and talking to him about Mexico and his wife and daughter there.

“Your dad’s not here,” Xavier said. “He drive out to the west lots.”

“I’m not looking for him.” Lacy climbed in the flatbed and watched him load tools.

“The Border Patrol came to Junior’s Boy Scouts,” she announced abruptly. “They’re rounding up Mexicans. But Mom said Dad worked it out.”

“Yes.”

“He did?” Lacy asked.

“He get us all papers.” Xavier stopped working. “Why? Why the sad face?”

“Nothing. My mom seemed…” Lacy didn’t put words to many feelings. They weren’t those kinds of people. “Weird,” she mumbled. “What papers?”

“Papers. To say the government knows you and you can be in America.”

“Why does the government have to know you?” she asked.

Xavier shrugged and loaded the truck.

“Why did they leave Mexico?” Lacy asked.

“Who?”

“The men in Chilitown. The workers.”

“Because.” He sighed. “Not everybody can live where he’s born.”

“How did they get here?”

“In trucks. Or walk and follow a star.”

Lacy looked down at the dress her mom made her wear, a stupid frilly thing from a shop in McAllen, and thought this over. “I was born here, but we’re moving to town.”

“Yes,” Xavier said. “I know.”

Lone Stars

Lone Stars